RICHARD KERN

(1954 – )

FILM :::

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, as downtown New York hovered between punk’s aftermath and art’s professionalization, Kern—working closely with Nick Zedd — helped define what became known as the Cinema of Transgression. It wasn’t a movement with a manifesto so much as a shared impulse: to cross lines because the lines themselves were fraudulent.

What “Transgression” Meant

The term, coined and articulated by Zedd, rejected the idea that cinema should reassure, redeem, or resolve. These films were short, raw, obscene, funny, violent, and immediate. They refused polish. They rejected narrative closure. They existed to confront the viewer with what polite culture preferred to suppress.

Shock wasn’t the goal. Exposure was.

Kern’s Films

The Right Side of My Brain (1983)

A fractured psychological portrait built from obsession, sex, and violence. Identity collapses. Meaning leaks. Nothing heals.

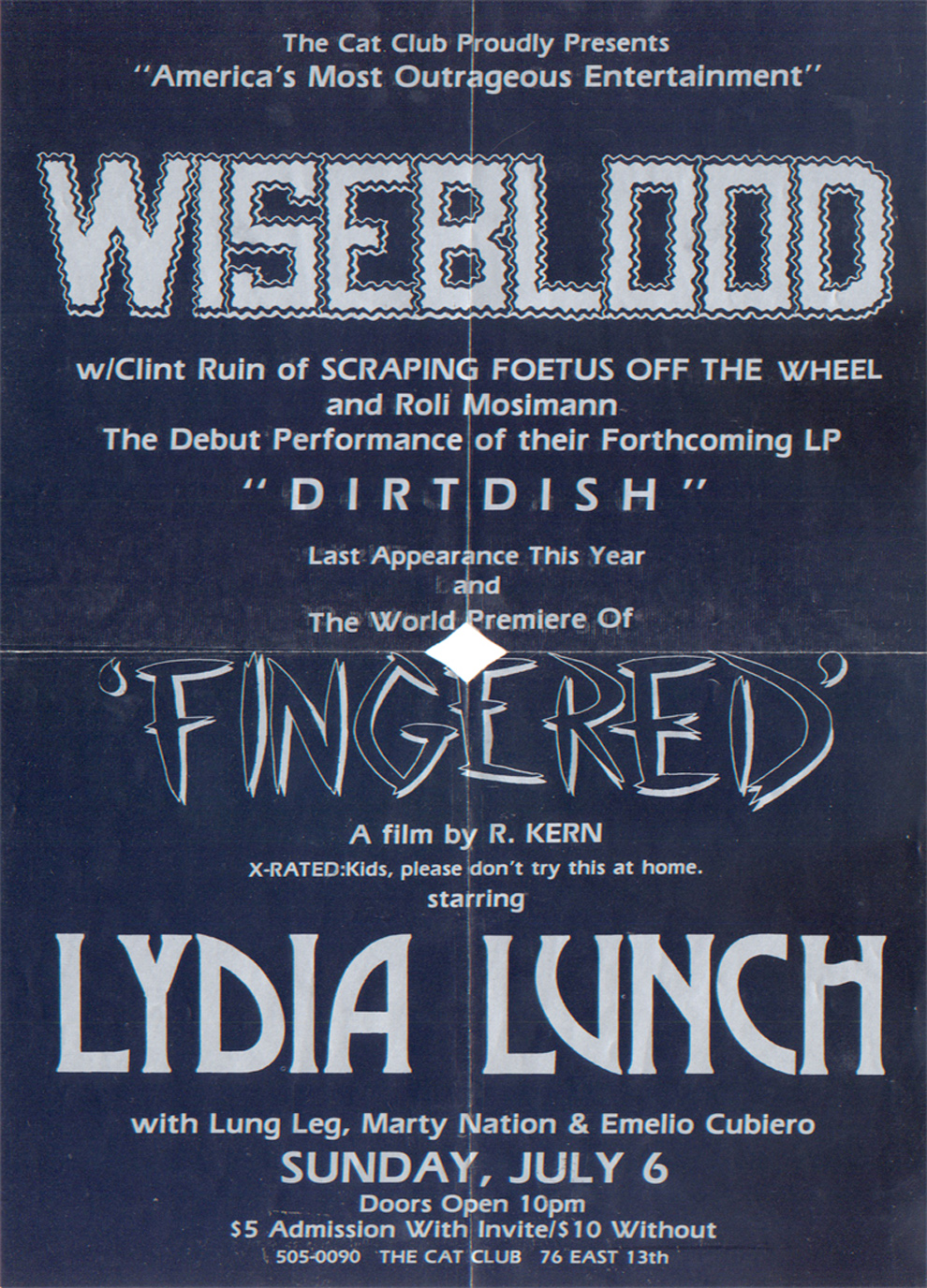

Fingered (1986)

Lydia Lunch as a woman pushed beyond victimhood into feral autonomy. The film doesn’t explain her rage or ask for empathy—it insists on it.

Kern’s aesthetic choices were intentional: grain as evidence, speed as urgency, ugliness as honesty. The films feel dangerous because they were made that way.

The Circle

Cinema of Transgression was inseparable from the people who inhabited it:

-

Lydia Lunch — intellect, fury, erotic violence

Nick Zedd — theorist, provocateur

Kembra Pfahler — endurance and body extremity

Sonic Youth — noise as structure

Karen Finley — spoken-word confrontation

Henry Rollins — physical sincerity

This wasn’t collaboration for prestige. It was shared risk.

From Film to Photography

In the 1990s, Kern shifted increasingly toward portrait photography. The images are cleaner on the surface, but the approach remains unchanged. His subjects—musicians, artists, outsiders—are presented without myth-making or protection. They meet the camera fully aware of being seen.

The confrontation becomes quieter, but no less direct.

Why It Endures

Cinema of Transgression occupies a crucial space in American underground art. It represents a moment when filmmakers rejected both commercial ambition and institutional legitimacy, choosing instead immediacy, offense, and truth on their own terms.

Kern’s work reminds us that some art isn’t meant to be absorbed gently.

It’s meant to test boundaries, fracture comfort, and leave a mark that doesn’t resolve.

No lessons.

No safety net.

Just exposure—

and the consequences of looking.